In Pavillion, a town of about 160 people in the heart of the Wind River Indian Reservation, the gas wells are crowded close together in an ecologically vivid area packed with large wetlands and home to 10 threatened or endangered species. Other than farming, there is no industry in the immediate area. They said the contaminant causing the most concern – a compound called 2-butoxyethanol, known as 2-BE – can be found in some common household cleaners, not just in fracturing fluids.īut those same EPA officials also said they had found no pesticides – a signature of agricultural contamination – and no indication that any industry or activity besides drilling could be to blame. They were careful to say they’re investigating a broad array of sources for the contamination, including agricultural activity. In interviews with ProPublica and at a public meeting this month in Pavillion’s community hall, officials spoke cautiously about their preliminary findings.

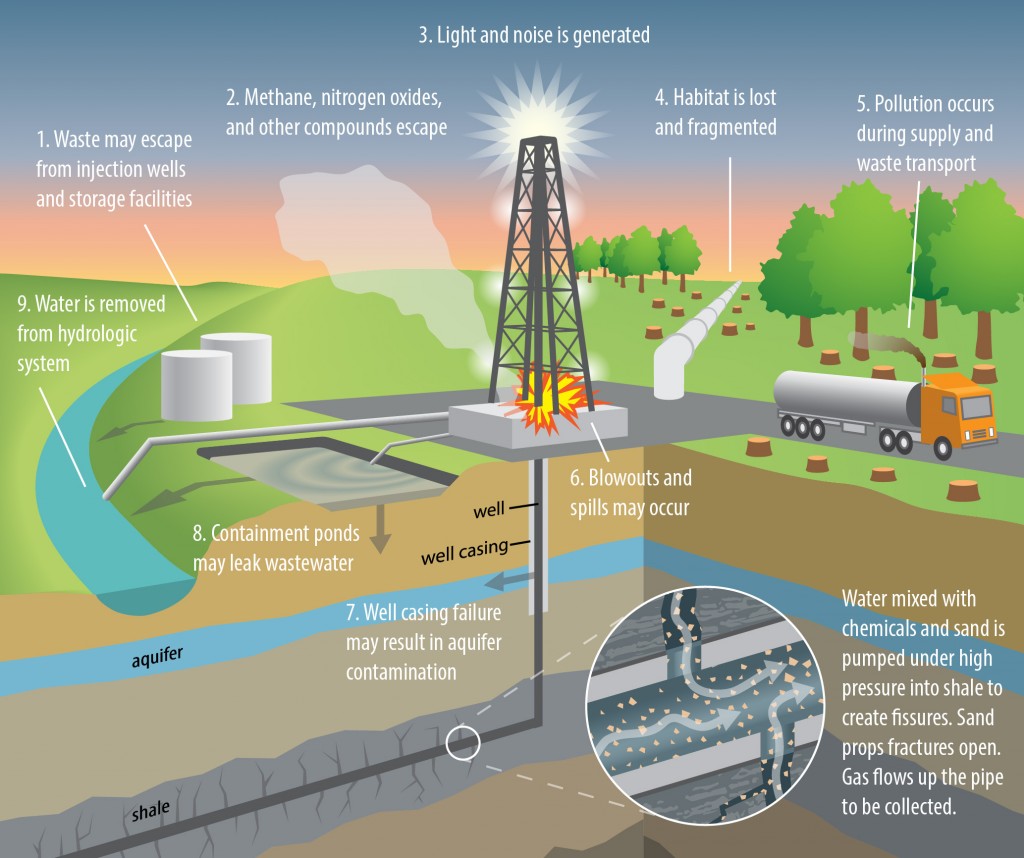

If they find that the contamination did result from drilling, the placid plains arching up to the Wind River Range would become the first site where fracturing fluids have been scientifically linked to groundwater contamination. Scientists in Wyoming will continue testing this fall to determine the level of chemicals in the water and exactly where they came from. But the industry says environmental regulation is unnecessary because it is impossible for fracturing fluids to reach underground water supplies and no such case has ever been proven. Congress is mulling a bill that aims to protect those water resources from hydraulic fracturing, the process in which fluids and sand are injected under high pressure to break up rock and release gas. The study, which is being conducted under the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program, is the first time the EPA has undertaken its own water analysis in response to complaints of contamination in drilling areas, and it could be pivotal in the national debate over the role of natural gas in America’s energy policy.Ībundant gas reserves are being aggressively developed in 31 states, including New York and Pennsylvania. Scientists also found traces of other contaminants, including oil, gas or metals, in 11 of 39 wells tested there since March. The logic is that offshore fracking has largely occurred in existing wells, locations for which companies already jumped through all the environmental hoops long ago.Federal environment officials investigating drinking water contamination near the ranching town of Pavillion, Wyo., have found that at least three water wells contain a chemical used in the natural gas drilling process of hydraulic fracturing. The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement – the federal regulator responsible for regulating offshore oil drilling – has issued “categorical exclusions” for fracking offshore California, essentially giving frack jobs a pass on environmental assessments.

This was largely unknown to California regulators and the general public. Related article: Peak Oil becomes an Issue Again after the IEA Revised its Predictionsĭocuments published through a Freedom of Information Act request showed that federal regulators have allowed drillers to dump chemicals into the ocean without an environmental impact statement assessing the effects of doing so.

#E.P.A. CHEMICALS FRACKING AGO NEW FILES SERIES#

The 1969 well blowout in the Santa Barbara Channel became the impetus for a series of environmental laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Water Act. Oil and gas companies have been fracking offshore California for perhaps as long as two decades, but they largely flew under the radar until recently.Īn Associated Press story in August 2013 revealed that oil and gas companies had engaged in hydraulic fracturing at least a dozen times in the Santa Barbara Channel – the site of the nation’s first offshore drilling site as well as the first major oil spill. Environmental Protection Agency published a rule on Janurequiring oil and gas companies using hydraulic fracturing off the coast of California to disclose the chemicals they discharge into the ocean.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)